How Architectural Innovations Can Safeguard Against Threats from Glass Buildings

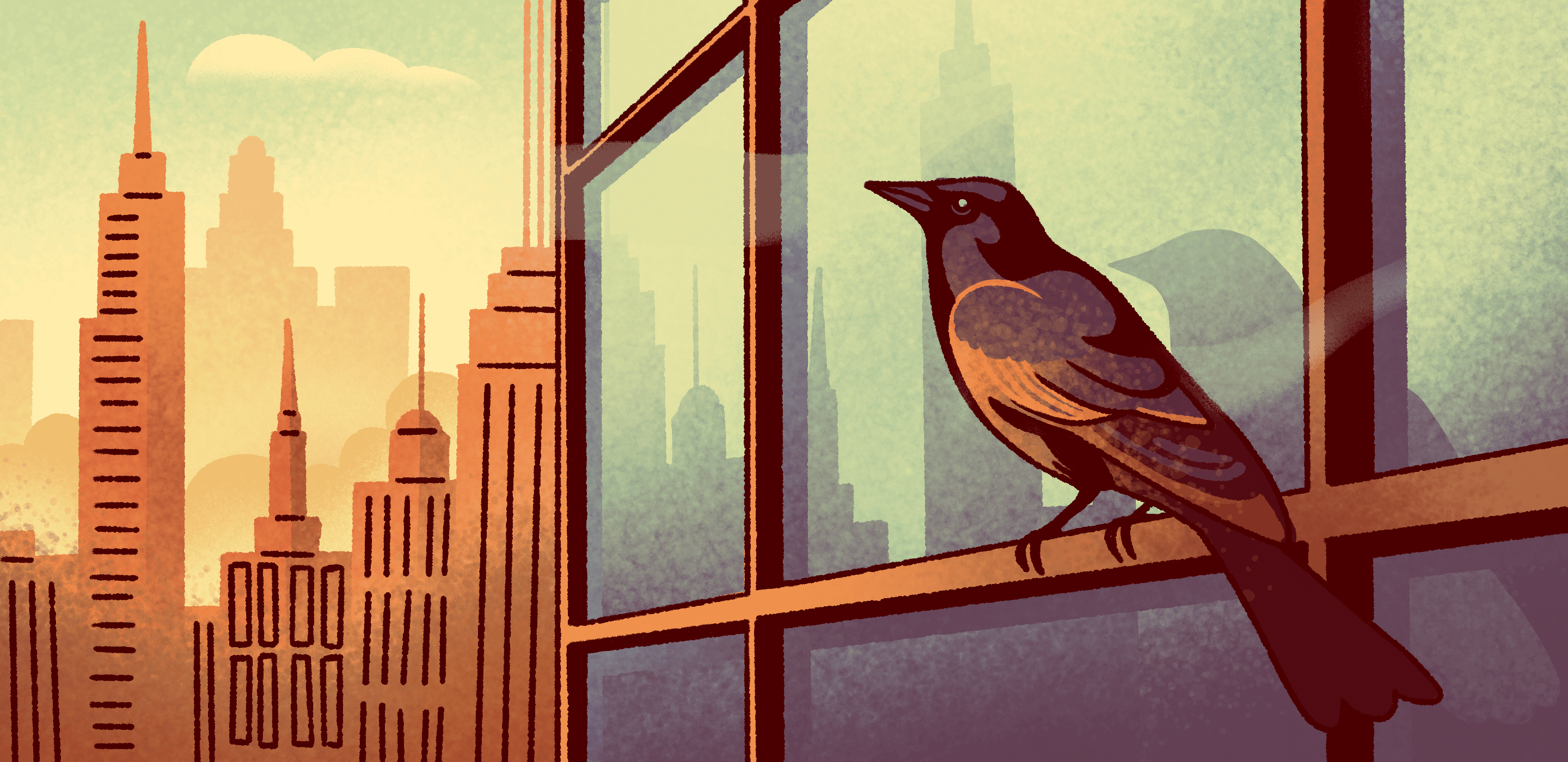

The haunting thud of a bird striking glass is a sound we all know. It’s so common, in fact, that building collisions claim the lives of up to one billion birds each year in the U.S. alone.

Birds represent far more than mere beauty; they are essential pollinators, controllers of pests, and stewards of ecosystems, fulfilling numerous roles vital to the health of our natural world. Yet, their populations are in decline. According to the State of the World’s Birds report, nearly half of all bird species globally are diminishing, with one in eight facing the threat of extinction. While habitat loss due to climate change, human encroachment, and predation by invasive species are significant factors, the built environment, particularly extensive glass surfaces, also plays a significant role in this decline.

Part of the problem is that birds don’t recognize glass the way we do. Where we see reflections of the sky and surroundings, they see extensions of their world—often with deadly results. Luckily, awareness of how certain design decisions affect the way birds see buildings is growing and progress is inching forward. Cities like Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and New York have adopted bird-friendly building standards, though federal legislation is trailing behind. There’s still a long way to go, but these cities show that such policies are not only possible, they’re also effective at preventing bird-window collisions. With a bit of urgency and goodwill, we could save millions of birds just by changing a few aspects of how we design our buildings and landscapes.

Here are the stories of two projects that are raising the bar on bird-friendly design:

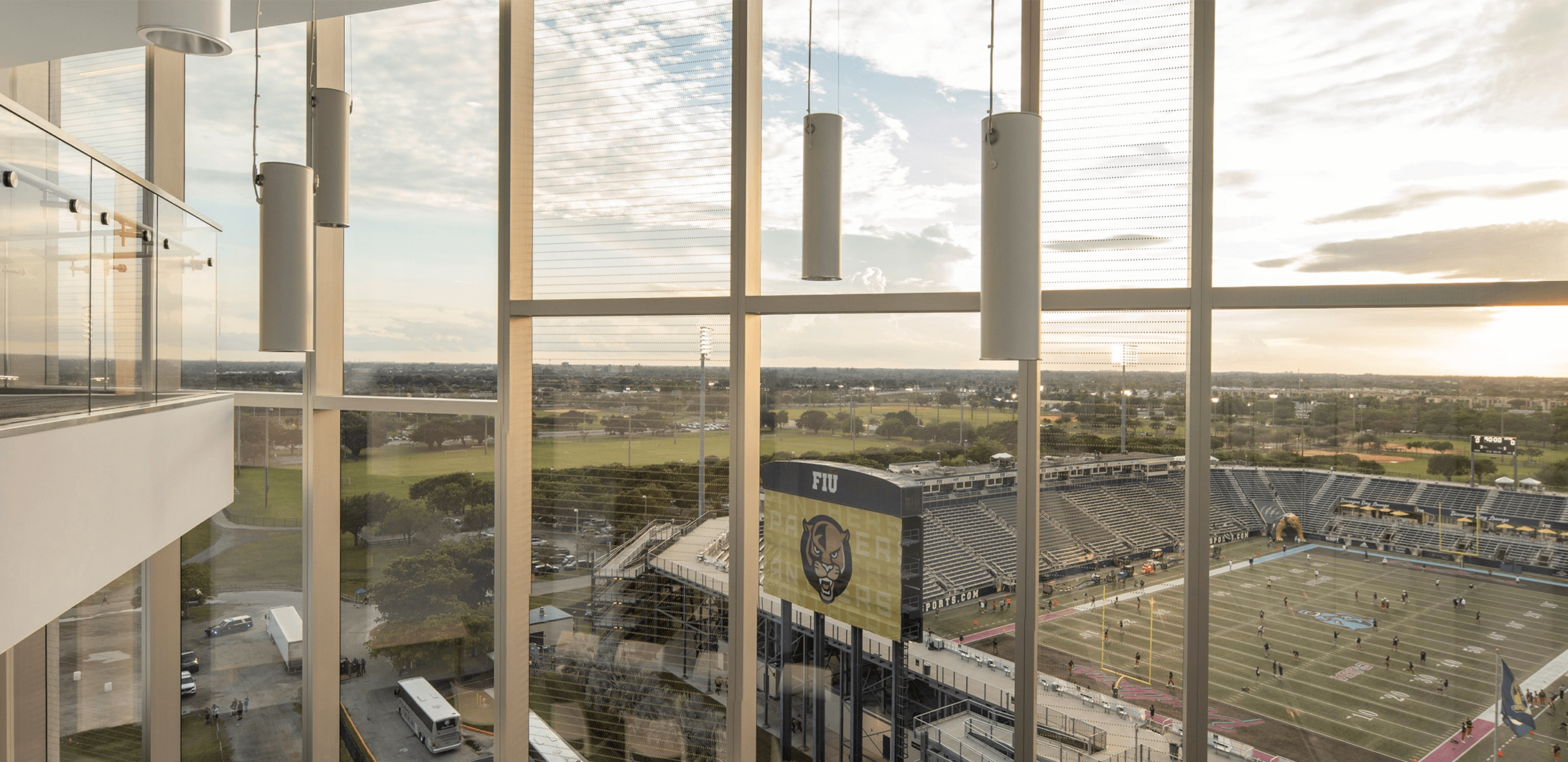

Project: Florida International University, Tamiami Hall and College of Engineering & Computing Center

Location: Miami, Florida

Amidst Miami’s skyline adorned with countless glass structures and its strategic position along Florida’s coast, serving as a migratory route for birds heading south, the city emerges as a perfect testing ground for bird-friendly design innovations. Embracing this opportunity, Florida International University (FIU), known for its commitment to environmental advancement, has undertaken initiatives to address the issue of bird fatalities resulting from collisions with buildings.

Birds in search of a safe place to rest or refuel often mistake reflections of treetops in windows for real perches. The first step in solving this problem is to make glass less transparent or mirror-like. At Tamiami Hall—a new student residence on FIU’s campus—the design team collaborated closely with the university’s department of architecture to implement a simple, yet astonishingly effective technique known as “fritting.” The process involves baking patterned ceramic paint onto the surface of the glass, creating visual cues that alert birds to the presence of a barrier, especially at tree-level and below where collisions are more common. This is in line with the American Bird Conservancy (ABC)’s “first 100 feet above grade” rule. Each floor of Tamiami Hall is also designed so that no room has glass on both sides, preventing birds from attempting to fly through the building. And what’s more, all treated glass reduces glare and cooling expenses by minimizing solar heat gain and visible light transmission.

But glass alone isn’t solely to blame. Artificial nighttime lighting, whether indoors or outdoors, disorients and confounds birds, worsening the situation. When buildings are brightly illuminated or when landscape lights cast upward, they intrude into birds’ migratory pathways, disrupting their navigation and leading them off course, often resulting in collisions with buildings. Moreover, excessive outdoor lighting contributes to light pollution, a concern also acknowledged by the astronomy department. To address these issues, FIU has instituted a ‘lights out’ policy after dusk, redirected outdoor lighting downward, and transitioned to a gentler red spectrum. Dr. Gray Read, an associate professor at FIU’s school of architecture, adds, “We’re taking these bold steps to tackle both the bird-friendly issue and light pollution.”

FIU President Ken A. Jessel has been a supporter of bird-friendly design from the get-go. All new construction on campus—including the soon-to-be College of Engineering & Computing Center—adheres to contract-mandated standards, such as the use of fritted glass, enforcement of a ‘lights out’ policy, and controlled inside and outdoor lighting. Dr. Read underscores that embracing bird-friendly design reflects the community’s commitment to ethical design and fosters a more harmonious campus environment.

“The whole push for bird-friendly glass doesn’t have to be some kind of trade-off, where birds win and architecture loses. Instead, it’s a chance to embrace a new design perspective. The ultimate goal is to reach a stage where bird-friendly design is just design.” ~ Carl Giometti, project architect

Project: University of Minnesota Bell Museum

Location: St. Paul, Minnesota

At the University of Minnesota’s Twin Cities campus, the Bell Museum takes visitors on a journey through the state’s natural history, exploring the intersections of art, science, and nature. With a collection of over 45,000 bird specimens, some showcased in fantastical dioramas, the Bell inspires a connection between environmental experiences of the past (within its walls) and the immediate present just outside, informing our collective future.

Situated along the Mississippi River, the U of M is home to a plethora of bird species that migrate northward in the spring. “It’s not just about bird-friendly design strategies being an option for nature and science-centered institutions; we all must consider the impact of our buildings on biodiversity,” says Dr. Holly Menninger, the museum’s interim director.

The design of The Bell is pivotal in reinforcing its natural history storyline. Incorporating sustainably sourced materials sourced from local suppliers, such as granite and panelized steel cladding inspired by the state’s mining legacy, alongside Forest Stewardship Council-certified thermally modified white pine siding, the building reflects a commitment to environmental responsibility. With less than 30 percent of its structure made of glass, all exterior glazing is designed with a bird-friendly pattern to minimize the risk of bird collisions.

The project’s success hinged on finding the right frit patterns, spacing, colors, and low reflectivity glass types. Two custom designs were used: one with closely spaced dots in select locations and the other with thinly spaced horizontal lines.

The dotted design, covering 40% of the glass area on the south, east, and west facades, serves a dual purpose. It deters birds in areas where human views of the outdoors aren’t crucial and reduces solar heat gain, thereby cutting energy usage and operational carbon emissions. Most of the glazing, however, uses a special bird-friendly pattern that the project team designed with the help of Owatonna-based fabricator Viracon and Audubon Minnesota. It features thin, high-contrast, medium-dark gray horizontal lines with 1-inch spacing. This glass treatment was applied to all facades where human views of the outdoors were a priority, as it not only effectively deters birds but is also visually appealing to visitors.

A lot of thought and intention went into the project’s bird-friendly design, stemming from local partnerships. For example, the Bell is involved in Project BirdSafe, an Audubon Minnesota initiative with the goal of reducing hazards to birds. The program’s volunteers have made significant strides in advancing our understanding of bird fatalities caused by glass collisions. “What materialized is a true reflection of who we are, our values, and how we show up in our community,” Dr. Menninger says. However, to obtain comprehensive data on where, when, and how birds are dying, wildlife conservationists are stressing the importance of backing from government agencies, NGOs, and professional scientists.

For years, green building practices have emphasized energy efficiency, sustainable materials, and resource conservation. Yet, the impact of buildings on birds and other wildlife often remains overlooked. A structure cannot genuinely be considered environmentally friendly if it disregards its surrounding ecology. While there’s no universal solution to ensure the safety of all birds, employing various design strategies such as utilizing fritted or opaque glass, minimizing the use of glass in construction, and managing indoor and outdoor lighting can foster better integration between built structures and the natural world.

“As architects, we’re not just designing places for people to thrive; we’re also building homes for other creatures. It’s an ethical challenge—we’re trying to connect with nature through glass, yet we’re inadvertently killing the wildlife we’re trying to admire.” ~ Doug Pierce, project architect